| Issue 2, November 2009 | Convention on Biological Diversity |

The medicinal and aromatic plants value chain in Saint Katherine, Egypt

[square brackets] is a newsletter focusing on the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and civil society. It aims to draw content and opinion from relevant individuals, organizations and members of civil society and provide information on issues of importance to the CBD, and on views and actions being undertaken by civil society organizations.

This edition is published to coincide with the eighth meeting of the Ad Hoc Open-ended Working Group on Access and Benefit-Sharing, 9-15 November 2009 in Montreal, Canada.

In this Issue:

Message from the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity

Message from the CBD Alliance

Part One: Articles

- ABS Negotiations: Sovereignty shall not be Compromised

- "If you help me to stand up I will walk the rest of the way”– Community-based Management of Medicinal Plants in Saint Katherine, Egypt

- Bio-cultural Community Protocols as a Community-based Approach to Ensuring the Local Integrity of Environmental Law and Policy

- Intellectual Property Rights in the Regime – The Hot Potato

- New Scientific and Technological Developments and the International Regime on Access to Genetic Resources and Benefit-Sharing

Part Two: Promoting an Exchange of Ideas

- Beth Elpern Burrows, President/Director, Edmonds Institute, Edmonds, Washington, USA

- Merle Alexander, Co-chair, Aboriginal Practice Group, Boughton Law Corporation, Vancouver, Canada

- Michael Frein, Environmental and trade policy adviser with the Protestant Church Development Service (Evangelischer Entwicklungsdienst - EED), Bonn, Germany

- Florina López, Regional Coordinator, Indigenous Women’s Biodiversity Network, Panama

Message from the Executive Secretary

Only with the involvement of all stakeholders can we achieve the goals of the Convention on Biological Diversity and bring a halt to the current staggering rate of loss of biodiversity. We are all stakeholders and the issues are complex. The 2010 International Year of Biodiversity provides an unprecedented opportunity to raise understanding of the importance of biodiversity to our lives, our future, and our resolve to act.

The CBD provides an indispensable and unique framework for action to safeguard biodiversity. The major piece of policy remaining to set in place is to enable implementation of the third objective of the CBD – access to genetic resources and the fair and equitable sharing of benefits that arise from their use. At its eighth meeting, in Montreal from 9 to 15 November 2009, the Ad Hoc Open-ended Working Group on Access and Benefit-sharing (WG ABS 8) will continue negotiation of an international regime on access to genetic resources and benefit-sharing.

Based on these negotiations, the tenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the CBD (COP10) to be held in Nagoya, Japan, will mark an historic point in the history of the Convention with the adoption of an instrument or instruments to effectively implement the access and benefit-sharing provisions of the Convention and those related to the equitable sharing of benefits arising from the utilization of traditional knowledge associated with genetic resources. At COP10 the international community will also have opportunity to agree targets and commitment to targets, post-2010, and a new strategic plan for the implementation of the Convention.

Civil society has an invaluable role in shaping opinion and policy and, through practical action, in implementing the CBD. The global network of the CBD Alliance serves to facilitate diverse and effective civil society involvement in the CBD processes. Nationally-based networks also have an invaluable part to play and in this respect, I am delighted to be establishing a memorandum of cooperation with the Canadian Environmental Network (RCEN) to support implementation and public outreach. In Japan, civil society has been active in preparations for COP10. Only a few months after its establishment, the Japan Civil Network for the Convention on Biological Diversity (JCN) was an important participant in the Kobe Biodiversity Dialogue in October 2009. It will play an important role in helping to shape the success of COP10 and the implementation of the Aichi-Nagoya Biodiversity Compact. Its establishment sets an example to be emulated by others, including India as the country offering to host COP11.

The interest and involvement of all of civil society will be crucial to ensure the success of the International Year of Biodiversity, a successful outcome of COP10, and the preservation of biodiversity for generations to come. It is my hope that this newsletter will contribute to gaining that full involvement.

Ahmed Djoghlaf, Executive Secretary, Convention on Biological Diversity

JCN for CBD – Japan Establishes Civil Network to help meet CBD Objectives

With the tenth Meeting of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (COP 10) and the fifth Conference of the Parties serving as the Meeting of the Parties to the Cartagena Protocol (COP-MOP 5) to be held in Nagoya, Aichi Prefecture in October 2010, the Japan Civil Network for the Convention on Biological Diversity (JCN for CBD) was established on 25 January 2009. The aims of the JCN for CBD are to: (1) establish a foundation for civil society to share information and ideas and promote public education, awareness and research on biodiversity and the CBD; (2) participate in the COP and COP/MOP negotiating process, acting as a focal point for international communities and disseminating information and recommendations concerning biodiversity nationally and internationally; and (3) to expand participation, communication and cooperation among national and international groups. Members comprise individuals and organizations from sectors including non-governmental organizations, business, research and education. The Executive Secretary of the CBD views both the JCN for CBD and the association established with the RCEN as examples to be emulated in other countries.

CBD Secretariat Partners with Canadian Environmental Network

To promote greater awareness of the Convention amongst civil-society organizations in Canada and abroad and to support the Convention’s implementation, the Secretariat signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with the Canadian Environmental Network (RCEN) on 10 November, 2009. The MoU establishes a collaborative framework between the SCBD and RCEN, which is an initiative comprising a network of more than 600 Canada-based civil-society organizations dedicated to improving environmental quality, including the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity. Cooperation will take place in several areas, which include: RCEN to act as host of the Canadian “Friends of the CBD” association for non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and support the SCBD in encouraging the establishment of similar organizations and promote twinning arrangements; Communication and outreach on biodiversity including the International Year of Biodiversity, International Day for Biological Diversity and The Green Wave. More>>

Message from the Board

Negotiations on the proposed International Regime on Access and Benefit Sharing (ABS) are a critical step towards the establishment of a legally-binding Protocol that, among other things, would end biopiracy, uphold the rights of the owners of genetic resources and the holders of traditional knowledge and honour their crucial contribution to the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity. Such critical objectives cannot be achieved through a voluntary mechanism.

Such a Protocol should support implementation of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIPs) in the international sphere. In negotiating a strong and effective regime, governments will demonstrate genuine commitment to the Declaration and to developing more just and equitable relationships with Indigenous People and local communities.

As asserted in several past joint civil society statements in ABS and COP negotiations, many civil society organizations believe that the principles of UNDRIPs must now provide the basis for, and establish minimal standards in the finalization of the draft text for the ABS Protocol. Respect for the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities over their territories, genetic resources and traditional knowledge is not only an important element of fair and equitable benefit-sharing but also a major contribution to all objectives of the Convention.For effective enforcement and implementation the ABS Protocol will have to ensure that legal systems in user country Parties guarantee that users comply with prior informed consent (PIC) and mutually agreed terms (MAT); and that rightsholders providing genetic resources and traditional knowledge are able to enforce their rights in user countries. And non-Parties should only be given access if they fully comply with all the standards of the Protocol.

As asserted in several past joint civil society statements in ABS and COP negotiations, many civil society organizations believe that the principles of UNDRIPs must now provide the basis for, and establish minimal standards in the finalization of the draft text for the ABS Protocol. Respect for the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities over their territories, genetic resources and traditional knowledge is not only an important element of fair and equitable benefit-sharing but also a major contribution to all objectives of the Convention.

It is obvious that such a major undertaking in international governance has to take care of many aspects and, by necessity, is complex. In this edition of [square brackets] we hope to address this complexity and to distil, at least at little bit, some of what is at stake in the negotiations by sharing the experiences and viewpoints of a broad range of civil society. We welcome comments and ideas about future editions.

Jessica Dempsey, co-cordinator for the CBD Alliance, on behalf of the CBD Alliance Board (www.cbdalliance.org)

(Please note, these comments do not reflect a consensus of civil society on the matter of Access and Benefit Sharing, but rather the individual views of the Board.)

Part One: Articles

ABS Negotiations: Sovereignty shall not be Compromised

By S. Faizi, Chairman of the Indian Biodiversity Forum; and, Prof. M Ravichandran, Head of the Department of Environmental Management of Bharatidasan University, Trichy, India ([email protected])

The issue of national sovereignty over biodiversity often comes up as a subject of criticism in access and benefit-sharing (ABS) parlance, and indeed in the discourse on the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). The life industry has never been able to live with it, but now a section of the Western media and scientists are also beginning to lampoon the sovereignty concept enshrined in the CBD. Various indigenous peoples’ groups have also, out of genuine concern, raised this issue, Their view is being vigorously amplified by some delegations, both inside and outside the negotiation halls, primarily because it gives them a legitimate handle with which to assail the sovereignty provision enshrined in CBD.

The unequivocal recognition of national sovereign rights over biodiversity did not come about easily in the Convention. It was the subject of protracted negotiations in the Inter-governmental Negotiating Committee, with developed countries arguing to legally place biodiversity as a global resource, and developing countries and civil society resolutely opposed to it. The life industry wanted to continue to have unregulated access to biodiversity across the world because they consider biodiversity to be a global resource. In addition, the TRIPS-compliant domestic patent laws of most countries disregard the national and community rights over the components of biodiversity and traditional knowledge that have been misappropriated to generate ‘novel’ products.

The critical legally binding provisions of CBD on prior informed consent for access to biodiversity and traditional knowledge, mutually agreed terms for access, equitable benefit-sharing, as well as the concept of country of origin of species are premised on the recognition (rather than assertion) of national sovereign rights over biodiversity. Those who challenge or doubt the sovereignty provision of the CBD are actually asking for an opening of the treaty for re-negotiation, which is tantamount to denouncing the treaty.

Challenge to Sovereignty

The forces of the globalization of capital incessantly challenge national sovereignty, seeking to replace it with corporate power. The World Trade Organization (WTO) agreements have eroded sovereignty by a significant level, reducing the freedom of nations to conduct affairs in crucial areas of national development. The ABS forum shall not be used as another platform for accentuating this erosion.

One method of the protagonists of the anti-sovereignty doctrine is to equate sovereignty with ownership. Sovereignty does not mean or imply governmental ownership; sovereignty and ownership (private, community) are by no means mutually exclusive but indeed complementary. Our small farmlands, for example, are our inalienable property, but the State comes to our rescue in the hypothetical event of a foreign power deciding to bomb our lands for some imaginary reason. Extinguishing sovereign protection of resources is unimaginable, for the resources could then be readily lost to the mighty corporates and we will have the frightening prospect of corporate sovereignty ruling the way resources are managed.

Greater role for indigenous people and local communities

Despite its ambience of good intentions about the indigenous people and local communities, the CBD fails to explicitly require Parties to involve them at all levels of management of biodiversity. That failure should not be repeated in the new ABS regime. It should have enforceable and verifiable provisions for factoring in the traditional rights of indigenous people over biodiversity and related knowledge, in line with the principles embodied in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Recognition of the territorial rights of the defeated indigenous peoples in countries ruled by settler populations ought to be reflected in the regime, if required, by incorporating the provision of shared sovereignty (rather than denouncing sovereignty). After all, recognition of national sovereignty is the fundamental principle upon which international cooperation is built.

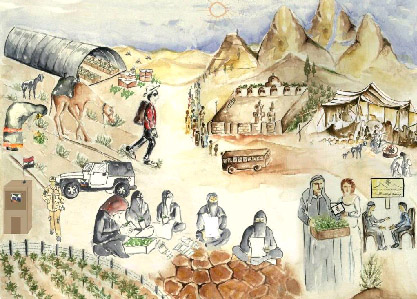

“If you help me to stand up I will walk the rest of the way” [1]

– Community-based Management of Medicinal Plants in Saint Katherine, Egypt

By Ossama El-Tayeb, Scientific Advisor, Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency; Omar Abdeldayem, Adel Tag Eldi, Ayman Hamada, and Kathryn Peacock of the Medicinal Plants Conservation Project, UNDP

Deliberations on access and benefit-sharing (ABS) issues, traditional knowledge (TK) and biological resources (BR) have important impacts on the international economic and legal context in which developing countries can frame their domestic policies for sustainable human development. . In the absence of appropriate national legislation people of developing countries have not been able to claim the right to prevent others from access or use of their biodiversity and TK. Each country should have the right to develop its own range of sanctions for breaches within its own jurisdiction.

In Egypt, the value of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants (MAPs), as one of the BR and associated TK, has raised concerns about the protection of the intellectual property rights of the Bedouin community of Saint Katherine, situated in South Sinai. The aim of the Medicinal Plants Conservation Project (MPCP), funded by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and implemented by the Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency (EEAA), is to develop and empower the local communities to conserve, sustainably use and benefit from Saint Katherine’s globally significant MAPs.

Creating an enabling environment for MAPs conservation and sustainable use will define and regulate the local community's rights to access their biological resources and to share the resulting benefits, to be achieved through an effective Egyptian national ABS legislation.

The MPCP took the following steps:

- A Ministerial Decree was issued for the formation of a scientific legal committee of experts representing various ministries, scientific institutes and organizations working in the field of ABS

- Numerous committee meetings have been held, featuring extensive negotiations between different stakeholders, in addition to reviewing all related national and international legislations

- Two national conferences were held, gathering local communities, herbalists, knowledge owners, relevant experts and stakeholders to help establish national legislation on access to BR and TK and the equitable sharing of the benefits of the management thereof.

A draft of the national ABS legislation is currently being reviewed by the ministers concerned with the purpose of submission to the legal authority for approval. This will regulate access to biological resources and traditional knowledge, with the community sharing in the benefits/revenues that arise from its use. The draft also comprises the necessary guarantees to ensure that the community receives these revenues, and that their rights are preserved, by registering BR and Bedouin TK in the national registry.

The essence of the draft Egyptian national legislation on ABS is:

- Make ABS regulations transparent, predictable and simple. Assure users equitable rights even in the long term, thus making biopiracy unnecessary for an honest, fair and serious bio-prospector

- Make ABS a strong incentive for the custodian of biological material and of related TK to continue conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity and effectively integrate ecosystem benefits, conservation and sustainable use into the fabric of local communities through benefit sharing

- Assist local owners of TK in the drafting of fair and equitable Prior Informed Consensus (PIC) and Mutually Agreed Terms (MAT)

- Encourage application of contemporary and emerging techniques for benefiting humanity from the potential of biodiversity, and of unique and extreme ecosystems, without sacrificing the rights of the custodians of such biodiversity and of the relevant TK of their ancestors

- Encourage and facilitate academic research in biodiversity and ecosystem management who do not seek commercialization as a primary objective

- Make biopiracy unnecessary for an honest, fair and serious bio-prospector, but to severely penalize bio-pirates and their accomplices through effective scientific documentation and tracking of biological resources and related traditional knowledge.

How international regime negotiators could help

Relevant help could come from the WGABS-8 negotiators by agreeing on a legally binding international regime. This would assure local custodians of TK and biological materials and their derivatives that their legitimate rights will be observed and honored by authorities in user countries Party to the international regime, in exchange for simple, inexpensive, predictable and equitable access based on principles of benefit-sharing between the owners of biological material and TK and the developers of its potential.

Novel approach involving local communities in conservation management and enhancing their livelihood

Saint Katherine is one of world's most amazing areas, not only for its natural landscape, but also for its medicinal plants diversity that attracts national and global interest. Of 472 species, 19 are globally significant, and more than 100 species are used for medicinal purposes. The Bedouin communities who live in the Saint Katherine Protectorate (SKP) have developed an extensive knowledge over the past millennia of the various ways in which medicinal plant species can be used. This in turn has formed a part of their integral economic value while living in a delicately balanced environment.

The development of a Community Based Natural Resources Management (CBNRM) system in SKP marks a new approach by the EEAA towards collaborative conservation. It can be considered as the most advanced formal CBNRM approach in the region. The main thrust for these interventions is to address the issues of tenure of, and access to, the MAP resources, thus ensuring that benefits are returned to those closest to the resource and who bear the costs of conservation management.

Since its establishment in 2007 the CBNRM program has made significant and notable progress:

- Establishment of a MAPs collectors association, which identifies 42 wild MAPs collectors, of which 40 are women. This represents the first time that women were included in deliberations when discussing issues of apportioning benefits and developing a Bedouin Tribal Law

- The CBNRM process has resulted in strengthening democratisation and accountability at the local level, and collaborates with Bedouin collectors and traders

- The constitution, rules and regulations of the MAPs collectors association was approved by the local community, SKP and the Nature Conservation Sector (NCS) of Egypt

- The program improved the SKP management plan and sets out the terms and conditions necessary for sustainable wild collection and trade

- MAP resources will be managed by the MAPs collectors Association based upon an official agreement between the community, SKP and NCS

- In order to improve the livelihood for the local community an innovative product line for wild MAPs was developed, organically labelled, and is being successfully marketed.

The Saint Katherine model is expected to serve as a model for community based biodiversity management in other parts of the country.

[1] “If you help me to stand up I will walk the rest of the way” - Bedouin idiom

Bio-cultural Community Protocols as a Community-based Approach to Ensuring the Local Integrity of Environmental Law and Policy

By Kabir Bavikatte & Harry Jonas, Co-Directors, Natural Justice: Lawyers for Communities and the Environment, Cape Town, South Africa

The next 12 months are an important period in the history of international environmental law for indigenous peoples and local communities (IPLCs). Negotiations under the auspices of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) are likely to culminate in two legal instruments that will have significant impacts on the lives of IPLCs, namely, the International Regime on Access and Benefit-Sharing (IRABS) and the programme on reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries (REDD).

The international regime will regulate the way traditional knowledge and genetic resources are accessed and how the benefits arising from their use are shared. REDD aims to contribute to the mitigation of climate change by facilitating payments for the non-logging of forests in which indigenous peoples and local communities live and depend on for their livelihoods.

Global in reach, local in implementation

Both international instruments are global in their reach, yet local in their implementation. In both the CBD and UNFCCC forums, IPLCs and NGOs are questioning the ability of the respective instruments to adequately respect and promote communities’ ways of life that have contributed to the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity. While international regulatory frameworks are important for dealing with modern global concerns such as biodiversity loss and climate change, their implementation requires careful calibration at the local level to ensure the environmental gains and social justice they are intended to deliver.

Environmental laws are most likely to generate local environmental and social benefits when Indigenous Peoples and local communities have the right of free, prior and informed consent over any activities undertaken on their lands or regarding access to their traditional knowledge and innovation and practices (TKIP). Without IPLCs’ input, there exists a danger that the laws intended to promote the overarching aims of the Rio Conventions to further undermine the local communities that have most contributed to the protection of biodiversity and least contributed to climate change. The legal and bio-cultural empowerment of IPLCs is therefore the indispensable condition of the local integrity of international environmental law.

In international law, the focus is often on protecting the environment

and IPLC's traditional knowledge, innovation and practices. But this is

often done without also empowering IPLCs to ensure the conservation and

sustainable use of their natural resources and the wider use of their TKIP

according to their bio-cultural values. Although there is a significant body

of work pertaining to sui generis systems of protection of TKIP and

associated genetic resources, significantly less emphasis has been placed on

devising means to ensure locally rooted holistic approaches to environmental

law.

Developing bio-cultural community protocols

The development of bio-cultural community protocols (BCPs) by indigenous peoples and local communities is one way in which communities can increase their capacity to drive the local implementation of international and national environmental laws. The process of developing a bio-cultural community protocol involves reflection about the inter-connectedness of various aspects of IPLCs’ ways of life (such as between culture, customary laws, community-based natural resources management, and TKIP) and may involve resource mapping, evaluating governance systems and reviewing community development plans.

It also involves legal empowerment so community members can better understand the international and national legal regimes that regulate various aspects of their lives, such as ABS, REDD, protected area frameworks, and payment for ecosystem service schemes. Taking ABS as an example, a community may want to evaluate on what terms it would engage with potential commercial and non-commercial researchers wanting access to their TKIP, what the community’s research priorities are, what would constitute FPIC, and what types of benefits the community would want to secure.

By articulating the above information in a bio-cultural community protocol, communities assert their rights to self-determination and improve their ability to engage with other stakeholders, such as government agencies, researchers and project proponents. These stakeholders are consequently better able to see the community in its entirety, including the extent of their territories and natural resources, their bio-cultural values and customary laws relating to the management of natural resources, their challenges, and their visions of ways forward. By referencing international and national laws, IPLCs affirm their rights to manage and benefit from their natural resources. They are also better placed to ensure that any approach for TKIP or for any other activity on their land, such as the establishment of a REDD project or protected area, occurs according to their customary laws.

Overall, BCPs help communities to reposition themselves as the drivers of conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity in ways that support their livelihoods and traditional ways of life.

(A book by the authors that deepens the above arguments, Bio-cultural Community Protocols: A Community Approach to Ensuring the Integrity of Environmental Law and Policy, is due for release in November 2009.)

Intellectual Property Rights in the Regime – The Hot Potato

By François Meienberg, Berne Declaration, Geneva, Switzerland

During past sessions of working- and expert groups, the issue of intellectual property rights (IPR) has always been one of the most challenging and contradictory, and therefore often avoided. One example was the technical expert group on compliance, where after a long debate, it was agreed to delete the whole paragraph on IPRs. This approach will not be suitable for the final negotiations. We have to handle the hot potato and eat it too!

There will be two chapters in the new protocol where intellectual property rights will play an important role: access and compliance.

Patents on genetic resources contradict facilitated access

Most discussions under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) on access to genetic resources - sometimes qualified as "appropriate" or "facilitated" access - focus on the first access to genetic resources in the country of origin. But in most cases there will be a chain of users, meaning a series of accesses. If there is something like a “facilitated access”, this has to be valid for all accesses, even after the genetic resource in question has left the country. It is a matter of fact that patents on genetic resources necessarily restrict continued access to them, as a patent holder has the explicit right to deny further access and use.

Therefore it is crucial to incorporate the solution of this problem into a future protocol. An example how this could be done is found in Art. 12.3. (d) of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture:

"Recipients shall not claim any intellectual property or other rights that limit the facilitated access to the plant genetic resources for food and agriculture, or their genetic parts or components, in the form received from the Multilateral System"

The ABS working group must elaborate a related article to be part of the new protocol. The wording of such an article should avoid the ambiguity of Art. 12.3 (d) of the International Treaty. Particularly the term "in the form received" should not be used. It has to be stated clearly that no IPRs shall be granted that restricts access to the original organism and its isolated components as well as for derived organisms and modified genetic material. If not, the whole CBD will lose its balance, forcing countries of origin to provide facilitated access but giving users patent rights that could prevent any further access for twenty years.

Intellectual property rights – A crucial checkpoint

Intellectual property rights (IPR) will also

play an important role in the compliance aspects of the protocol.

There is already specific wording under “Disclosure requirements”

and “Identification of check points” in the text under negotiation.

Some may argue that disclosure of compliance during the application

procedure for IPR will not make sense, if a new protocol were to

prohibit any intellectual property rights that limit the facilitated

access to genetic resources (see above). This is not true as many

patented inventions are based on genetic resources but do not

contain the genetic material any longer (e.g. a new drug).

The discussion on this issue is not new and the

opposition of many developed countries and industry against such

disclosure requirements is well known – although it is still hard to

understand. Why is there a problem to disclose something you already

have to comply with? Or in other words: Why should we allow patents

or plant variety protection certificates which are in contradiction

to international law?

In the financial sector, Switzerland has played a similar role as

many patent offices in relation to ABS. For many years Swiss Banks

have been a safe haven for foreigners evading taxes, just as patent

offices have paved the way for the commercialization of biopirated

genetic resources. But times are changing. Switzerland has been

under tremendous pressure from other OECD countries to disclose the

bank accounts of tax evaders, and Switzerland is giving in, step by

step. And increased pressure is to be placed on patent offices

supporting biopirates breaking the ABS laws of other countries.

Sooner or later they will have to step in and ask for the disclosure

of origin and the compliance with foreign laws or the protocol. It

is hard to argue that there should be disclosure if there is a

problem with (tax-) laws of developed countries, but denying this

disclosure if there is a problem with (ABS-) laws from developing

countries.

There is another kind of one-sided view related to this question. Several developed countries say that questions related to IPR should not be discussed under the CBD, but at the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). But exactly the same countries were at the centre of negotiations when IPRs were integrated into the World Trade Organization (WTO) within the TRIPS agreement. And the same countries are always integrating chapters about IPRs in their Free Trade Agreements. There is clearly a double standard here: when it is in the interest of strengthening their IPRs (and that of companies in it) northern countries insist on it being in the agreement, but when it is against their interests they disagree and say it should be negotiated elsewhere.

New Scientific and Technological Developments and the International Regime on Access to Genetic Resources and Benefit-Sharing

Manuel Ruiz Muller, Peruvian Society for Environmental Law (SPDA), Lima, Peru

Access to genetic resources and benefit-sharing (ABS) have, once again, become highly contentious in international environmental and development debates and agendas. The ongoing negotiation of the International Regime (IR) on Access and Benefit Sharing under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) has made conflicting developed and developing countries views ever more apparent. The completely bracketed text of the current draft of the IR reflects this. The IR will, hopefully, establish a framework under which ABS aspects and issues which require multilateral responses will be addressed. These may include enforcement measures, specific actions by countries using and receiving genetic resources, among others. As important as advances in the IR process may be, an absent feature in its current draft form and in ongoing debates, relates to new scientific developments and technologies related to genetic resources. Bioinformatics, genomics, proteomics, proboleomics, synthetic biology, new genetically engineered products and processes, etc. are all paving the way for innovation and new knowledge related to biodiversity. However, their inclusion in the IR debates has been marginal at best.

Policy and legal advances in ABS

In terms of policy and legal developments in ABS (and related traditional knowledge), since the entry into force of the CBD in 1993, considerable progress has been made. Laws and policies in the African Union, the Andean Community, Brazil, Costa Rica, India, Panama, Peru, Philippines, etc. have sought to establish measures to ensure fairness and equity in the sharing of benefits derived from accessing and using genetic resources (Carrizosa, 2004). But these advances are based on a long passed paradigm which considers genetic resources as unique, distinct, physical material obtained from the rainforest or from some exotic source elsewhere.

Whilst important businesses are evolving in natural products development (with limited added value to actual raw materials), where these policies and laws may be applicable, there are critically important areas of innovation which are making use of genetic information and transforming how research and development takes place (Vogel, 1992). It is here where bioinformatics (the combination of computer technology with biochemistry, molecular biology and intensive use of information) and new technologies are revolutionizing the manner and process in which science progresses. This often unaccounted for scenario is critical in terms of benefit generation from genetic resources. How and whether the IR will address some of these issues, will probably determine its relevance and success.

New technology and scientific advances: the challenges for the International Regime

Debates in regards to bioinformatics, genomics, proteomics, etc., have taken place in very focalized scientific and academic circles, plus in the context of intellectual property and patent coverage in particular (Oldham, 2004). The tension between privatization trends (the “enclosure movement” (Boyle, 2003) and the opposing movement supporting open source, copy left, knowledge commons, public goods, creative commons, etc., has led to very interesting exchanges and enlightening debates between those supporting strong IP to stimulate innovation and those arguing for strong research exemptions and a healthy knowledge commons (Hess and Olstrom, 2007), especially in the field of biodiversity related research. The recent Economics Nobel laureate, Elinor Ostrom and her work on the commons, has put some of these debates in the spotlight.

Box 1. Scope and coverage of the ABS International Regime: how far ?

| Issue | ABS policy and legal focus (PIC, MAT, benefit sharing) | Tools and means to transform, innovate, create … | Products and processes |

| Scope | Biological, tangible materials | Bioinformatics Genomics Proteomics Synthetic biology Genetic engineering Other technologies |

Identification of species Data bases Bar codes Active compounds Pharmaceuticals Seed varieties Other products |

| Nature | Physical nature | Based on interpreting data and information (including genetic information) | Tangible, sometimes informational products |

| Rights | Sovereignty, community rights, property | Intellectual property | Intellectual property |

In this regard, it is valid to ask where exactly does this debate fit within the IR ABS negotiations or whether the IR is capturing some of its features and addressing them as part of its substance. Or even if it is relevant to the IR, which we think it is (Pastor and Ruiz, 2008).

Value and benefits from biodiversity are clearly not limited to the raw, physical biological materials accessed and used. This is especially true even though it is the markets of natural products (creams, oils, vitamin supplements, foodstuffs, etc.) were economic benefits are more “visible”. However, often scientific and economic value lie in the process through which genes are identified, proteins codified, specific gene functions determined, evolutionary relations established, active compounds identified, molecules understood or synthesised, drugs produced, etc. The immediate question is who has rights during the different stages of these processes and over the different innovations therein, and whether sovereignty of States is relevant and enforceable in practice along this process. This is critical given these different tools and disciplines are, ultimately, using biological or genetically derived components to generate knowledge, innovations and products.

Final remarks

As part of the ongoing IR negotiations, countries should take careful note of and respond through sound measures to how science and technology are evolving and transforming the scientific process altogether. Data, information and interdisciplinary efforts are paving the way to new developments in biodiversity research. Genetic resources are not tangible – strictly speaking or, at least, there value lies in their informational nature. Indeed, biodiversity research is based, as a starting point, on biological material obtained from a wide range of very varied sources – from hydro thermal vents to a farmers plot or a protected area. These are certainly areas under the scope of the IR. But more sophisticated research and innovation processes which are transforming biodiversity and where the “distance” between original materials and products is considerable, and where information is the key element, are still part of a complex ABS scenario where policy and laws should, carefully, intervene. Intellectual property rights is an area of law now fully engaged in regulating these fields, so maybe it is appropriate for the ABS IR to do likewise (Pastor, 2006).

References

Boyle, James. 2003. The Second Enclosure Movement and the Construction of the Public Domain. Duke University, US.

Carrizosa, Santiago, Brush, Stephen, Wright, Brian, McGuire, Patrick. 2004. Accessing Biodiversity and Sharing Benefits: Lessons from Implementing the Convention on Biological Diversity. IUCN Environmental Law Policy and Law Paper No. 54. Gland, Switzerland.

Hess, Charlotte and Ostrom, Elinor (Eds). 2007. Understanding Knowledge as Commons: From Theory to Practice. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, USA.

Oldham, Paul. Biodiversity and the Patent System: An Introduction to Research Methods. Initiative for the Prevention of Biopiracy. Research Document. Year II, No. 6, March 206. Available at: http://www.biopirateria.org

Pastor, Santiago y Fuentealba, Beatriz. Camélidos, Nuevos vances tecnológicos y Patentes: Posibilidades y Preocupaciones para la Región Andina. Año II, No. 4, Enero 2996. Disponible en http://www.biopirateria.org

Pastor, Santiago and Ruiz, Manuel. The Development of an International Regime on ABS in a Context of New Technological Developments. Initiative for the Prevention of Biopiracy. Year IV, No. 10, April 2009. Available at: http://www.biopirateria.org

Vogel, Joseph. Genes for Sale. 1994. Privatization as a Conservation Policy. Oxford University Press. New York.

Part Two: Promoting an Exchange of Ideas

To promote an exchange of viewpoints on ABS, the editorial board posed five questions to civil society actors.

(Please note that the CBD Provisions referred to in question 3 can be found at the end of the section.)

| Beth Elpern Burrows - President/Director of the Edmonds Institute, a public interest organization focused on environment and technology and based in Edmonds, Washington, USA |

1) What is the problem we are trying to solve with this regime?

To help ensure that all Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity operationalize and implement their ABS obligations under the Convention, particularly, although not limited to, the obligations that are implied in Article 15 and Article 8(j).

2) What will be the main parts of a future regime to achieve this goal?

Among the issues to be resolved are those that involve:

- Objectives of the regime

- Use (definition) of terms

- Scope (including limitations and exclusions) of the regime

- General provisions clarifying national sovereignty over genetic resources and indigenous and local rights over traditional knowledge

- Acceptable procedures in the access and benefit sharing process (including timing and deadlines)

- Acceptable procedures for obtaining free and prior informed consent, including standards and requirements for mutually agreed terms

- Procedures for monitoring, reporting, and verifying agreements and transgressions

- Procedures and venue assignment for settlement of disputes, including details of compliance and incentive mechanisms and methods of dealing with violation

- Funding arrangements for the regime, including arrangements for the time before the regime comes into force and commitments for capacity building, including national capacity building, indigenous and local community capacity building, and capacity building for scientific and academic stakeholder communities Procedures for ratification and adoption of the regime

- Procedures for amendment of the regime

- Procedures for accession to and withdrawal from the regime

- Standards for the regime to come into force

- Decisions about reservations to the regime

- Standards and clarifications for administration of the regime at the international, national, regional, local, and indigenous levels.

3) Why have the ABS provisions of the Convention not yet been widely implemented by the Parties?

Among the many reasons for lack of implementation are these:

- The meaning and desirability of the CBD’s provisions are not clear to all

- Some non-Parties and interest groups lobby against national sovereignty over genetic resources; some resent the changes that such sovereignty implies for their once unquestioned privileges (e.g., of unimpeded access), some worry that such changes will be costly in terms of time and money and ability to sustain their own agendas and some simply find the idea of sovereignty over resources to be repugnant

- Some Parties and non-Parties resist recognition of indigenous and local rights to free and prior informed consent

- Some Parties and some indigenous peoples and local communities do not have or may not want the legal infrastructure necessary to implement an effective ABS regime

- The cost of implementation of ABS provisions is greater than many can bear and the availability of politically neutral and effective capacity building is not at all guaranteed

- Implementing a new regime that may be difficult and costly may not be perceived as sufficiently beneficial to warrant a high rank on already-too-lengthy political, economic, and environmental to-do lists.

4) What are the main challenges/obstacles on the way to finalize the text of the regime?

The main obstacles have to do with fact that not all the ABS players seek the same goals. Some hope for a regime that guarantees certainty of access while others insist on a regime that ensures certainty of benefit. Some hope for no regime at all, in some cases seeking to avoid further regimes of outsider access and in other cases seeking to prolong their own unfettered access to the domains of others. While many resist ineffective regimes, others resist only regimes that would be legally binding on themselves. While some yearn for a regime that sustains the viability of their ecosystems and their lives, others push for a regime that enhances the reach of their sovereignty and/or their trade agreements. All resist a costly regime, despite the fact that any regime that is fair and equitable will most certainly be precedent-setting and therefore costly. Finally, while some bravely pursue the way forward, others seem to have lost the way entirely. They apparently no longer believe that the CBD can stem the loss of biodiversity and spur its Parties to use, share, and preserve the astonishing bounty of their most magnificent planet.

5) What is your wish for WG-ABS 8 in Montreal?

That all who want to preserve and sustain biological and cultural diversity are enabled to attend; and, that all who do attend, intend to:

- Understand the needs and positions of others

- Consider that their own goals, as meritorious as they may be, are not necessarily the best or the highest goals for all

- Forget the pretensions of their professions and the prerogatives of their past

- Create and sustain the conditions for a respectful and fair and equitable ABS regime

- Share to the maximum extent possible the costs and work of implementing whatever is agreed upon

- Remember why this meeting was made necessary in the first place

- Act as if the last ray of hope for our species and many others resides in the outcome of this meeting and to act accordingly.

| Merle Alexander - Member of Kitasoo Xai'xais First Nation, Tsimshian Nation, in British Columbia, Canada, Co-chair of the Aboriginal Practice Group, Merle Alexander practices corporate/ commercial law with a focus on Aboriginal sustainable development, which balances economic development, respect for Aboriginal rights and environmental conservation for future generations. |

1) What is the problem we are trying to solve with this regime?

Misappropriation of genetic resources and associated technical knowledge from sovereign States and sovereign Indigenous Peoples. A voluntary regime that is not applied consistently throughout jurisdictions allows the unscrupulous to “jurisdiction shop”. That is, persons or legal entities that seek to bypass the Bonn Guidelines simply exercise their rights to misappropriate genetic resources or traditional knowledge in a jurisdiction that has minimal or no ABS regime, such as Canada.

2) What will be the main parts of a future regime to achieve this goal?

A binding regime will demand international compliance for CBD Parties and require Parties to develop consistent national legal standards. If there is a new Protocol or binding treaty developed, Canada will be hard pressed not to ratify or adopt such a protocol or treaty. This will thereby require Canada to do a substantive consultative process in the development of ratifying legislation and any national legislative model will be subject to Canadian constitutional law, including the application of Section 35, Constitution Act, 1982, that sets out a legal duty to consult/accommodate/consent with applicable Aboriginal peoples.

3) Why have the ABS provisions of the Convention not yet been widely implemented by the Parties?

Perhaps two reasons: (1) perception by most Parties that genetic resources and technical knowledge are not being exploited; and (2) voluntary regimes only encourage proactive Parties to implement.

4) What are the main challenges/obstacles on the way to finalize the text of the regime?

Good faith of all Parties to negotiate; time and financial resources. It is fair to state there are certainly some Parties that have instructions to avoid an ABS International regime at all costs, yet they are at the negotiation table. They are negotiating against an IR. Time - even for all Parties acting in the best of faith, there does not appear to be enough time at the Working Groups to complete substantive negotiations. There are also Parties acting in bad faith that are intentionally attempting to run out the clock. Financial - for developing countries and Indigenous Peoples there needs to be an immediate insertion of financial resources into the process to ensure that there is a level playing field, especially against those with unequal bargaining power.

5) What is your wish for WG-ABS 8 in Montreal?

That Indigenous Peoples’ legal perspectives will be truly reflected in the outcome text of the meeting. This will require assistance of support by the EU and African Group. The African Group cannot do it alone.

| Michael Frein - Environmental and trade policy adviser with the Protestant Church Development Service (Evangelischer Entwicklungsdienst - EED) in Bonn, Germany. |

1) What is the problem we are trying to solve with this regime?

The negotiation process is essentially about justice. On the one hand it deals with North-South-justice, on the other hand it is about justice for the people, mainly in provider countries, via-à-vis their own governments and the users. Regarding the second aspect, the question of human rights, as covered in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, must be taken up in the negotiations.

The main obstacle when dealing with the problem of justice is the position of those users and user-countries who intend to stick to the unacceptable principle of free access to genetic resources and related traditional knowledge or to frame their activities as close as possible to that principle. For hundreds of years, users had an unconditional access to genetic resources and associated traditional knowledge. In a world where the means to use these resources and to derive benefits from them are distributed in an unequal manner, unconditional access to genetic resources aggravates the current situation that is already characterized by severe imbalances. The international regime has to provide a rebalancing. In this process the provisions of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples should form a baseline.

2) What will be the main parts of a future regime to achieve this goal?

Those who control access also have a crucial say in benefit sharing. This is one of the reasons why some parties favour access rules with minimum standards and on a non-discriminatory basis. In a users’ perspective benefit sharing might lead to additional costs, which is not seen to be favourable, but acceptable, if in the first place the access doors remains widely open. Therefore, for the regime, access rules are needed that not simply intend to bring the genetic resource and the traditional knowledge to the respective user as quick and cheap as possible but are to strengthen the bargaining power of providers.

Additionally, there have to be user measures preventing misuse and misappropriation. Patenting, marketing or research, for instance, should only be allowed if the respective use is in accordance with the use determined in the mutually agreed terms. This is why first a differentiated certificate of compliance is needed and second, in case of non-compliance a withdrawal of former approvals accompanied by further compensations for the providers and penalties are necessary.

This system should apply to traditional knowledge in analogy. Only by controlling access, indigenous peoples and local communities will have a control on the use of their knowledge and their resources. This means, that the procedure of Free and Prior Informed Consent has to be compulsory, including the right to say “No” and thus deny access in cases where it deems to be unacceptable.

3) Why have the ABS provisions of the Convention not yet been widely implemented by the Parties?

One reason is that user countries aim at keeping the principle of unconditional access as long as possible. In the course of the negotiations, the respective strategies of users and user countries to prevent the implementation of the CBD rules ranged from blunt opposition to any ABS rules, denial of the need for binding rules to demanding extensive gap analyses to keep the negotiation process busy with other work than implementing the CBD provisions. Remarkable in this context are extensive debates on the question if it is the business of the Working Group to negotiate or not.

Another problem lies with those governments demanding justice while at the same time they deprive indigenous peoples and local communities of their human rights, be it by law or in practice. The strategy, accusing user countries for biopiracy and misappropriation of traditional knowledge and simultaneously not accepting the rights of indigenous peoples is incoherent. It serves the game of those countries who intend to decelerate the process.

4) What are the main challenges/obstacles on the way to finalize the text of the regime?

The main challenge is the position of some corporate bodies in user countries. Companies want to ensure a cheap and quick access, avoiding access procedures which are seen as too long, too complicated and at the end of the day too expensive. But also some scientists see their freedom of research endangered.

Another obstacle is closely connected to the implementation of the rights of indigenous peoples. In fact, any party that denies the existence of indigenous peoples or denigrates the whole issue of rights of indigenous peoples, is an obstacle to a successful outcome.

Therefore, those parties who fall under one or both mentioned categories will belong to the critical actors in Montreal.

5) What is your wish for WG-ABS 8 in Montreal?

There is breakthrough needed, mainly in three areas. First, acceptance of and support for the rights of indigenous peoples, as they are covered in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples by all Parties has to be achieved. The respective paragraph in the draft article on scope must be maintained in its most comprehensive version.

Second, a common understanding that the term “facilitated access” does not merely mean minimum standards or non-discrimination. ”Facilitated access” rather means that governments provide procedures to enable users to gain legal access on the basis of the CBD provisions and thus improving the current situation which is characterized by legally unsecure or even illegal access.

Third, user countries should be ready to accept user measures that include the obligation for a new Prior Informed Consent in case of a new use, making a certificate of compliance effectively workable in order to prevent any misuse or misappropriation. In cases of non-compliance, measures with discouraging impacts must be in place for those users who wish to make an extra benefit by misuse and misappropriation.

|

Florina López - Regional Coordinator with the Indigenous Women’s Biodiversity Network, Panama |

1) What is the problem we are trying to solve with this regime?

The main problem that this regime must solve is how to regulate access to genetic resources through a legally binding instrument. One that respects and recognizes the rights of the indigenous peoples that implement the articles of the Convention; while simultaneously safeguarding and promoting the third objective of the CBD – the fair and equitable sharing of the benefits from the use of genetic resources. The regime must also include the legal origin of these resources, and the prior informed consent of the owners or suppliers of the genetic matter for the request and granting of patents, through mutually decided terms. For many years there has been an imbalance between developing countries (suppliers), and developed countries (users) as far as economic benefits and transfer of technologies are concerned.

Indigenous peoples’ control over genetic resources is under attack. Pharmaceutical corporations, research institutions and a lack of coherent policies by States are resulting an invasion of indigenous territory. The resources of indigenous peoples are being exploited without their consent or their participation in these benefits.

2) What will be the main parts of a future regime to achieve this goal?

For indigenous peoples the main part will be the recognition of the rights of indigenous peoples to participate in the equitable distribution of benefits. And above all to respect and ensure the implementation of free prior and informed consent; and to have access to genetic resources and other resources on the lands and territories of indigenous peoples intrinsically linked to traditional knowledge.

3) Why have the ABS provisions of the Convention not yet been widely implemented by the Parties?

Because in developed countries, as developing countries have not reached agreement, each sector prioritizes their own interests, and in the midst of it all indigenous peoples are observers, since they do not want to recognize our rights as owners and as those who have long maintained and preserved these resources for themselves and for the rest of humanity.

4) What are the main challenges/obstacles on the way to finalize the text of the regime?

The biggest challenge for us in finalizing the text is for the owners of genetic resources to participate in the discussion, negotiation and drafting of the regime, based on the Declaration of Indigenous Peoples and international conventions. Since most of these resources lie within the territories of the indigenous people, it will be very difficult to develop a regime which recognizes their rights without their full and effective participation.

5) What is your wish for WG-ABS 8 in Montreal?

The aspiration of indigenous peoples is that the meeting takes into account the proposals we have been negotiating; the proposals from our people, organizations, and from the International Indigenous Forum on Biodiversity.

Provisions referred to in question 3 are CBD articles:

15.1. Recognizing the sovereign rights of States over their natural resources, the authority to determine access to genetic resources rests with the national governments and is subject to national legislation.

15.4. Access, where granted, shall be on mutually agreed terms and subject to the provisions of this Article.

15.5. Access to genetic resources shall be subject to prior informed consent of the Contracting Party providing such resources, unless otherwise determined by that Party.

15.7. Each Contracting Party shall take legislative, administrative or policy measures, as appropriate, and in accordance with Articles 16 and 19 and, where necessary, through the financial mechanism established by Articles 20 and 21 with the aim of sharing in a fair and equitable way the results of research and development and the benefits arising from the commercial and other utilization of genetic resources with the Contracting Party providing such resources. Such sharing shall be upon mutually agreed terms.

Editorial Board

Estebancio Castro Diaz -

International Alliance of Indigenous and Tribal Peoples of Tropical

Forests

Jennifer Corpuz -

Tebtebba (Indigenous Peoples' International Centre for Policy Research

and Education)

Jessica Dempsey -

CBD Alliance

S Faizi - Indian

Biodiversity Forum

Francois Meienberg -

Berne Declaration

Valerie Normand -

Convention on Biological Diversity

Neil Pratt -

Convention on Biological Diversity

John Scott -

Convention on Biological Diversity

Director of Publication

Ravi Sharma - Convention on Biological Diversity

Managing Editors

CBD Secretariat

Neil Pratt

Johan Hedlund ([email protected])

CBD Alliance Jessica Dempsey

Comments and suggestions for future columns are welcome and should be addressed to:Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity

413 St. Jacques, Suite 800, Montréal, Québec

H2Y 1N9 Canada

Tel. +1 514 288 2220 | Fax: +1 514 288 6588

[email protected]

www.cbd.int

This newsletter aims to present a diversity of civil society opinions. The views expressed in the articles are the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity, its Secretariat or the CBD Alliance.

Convention on Biological Diversity - www.cbd.int

Access and Benefit-Sharing - www.cbd.int/abs

Article 8(j): Traditional Knowledge, Innovations and Practices - www.cbd.int/traditional

CBD Alliance - www.cbdalliance.org